On this page:

Dr. Shona shares how to use graphic organizers in the classroom for informational, argumentative and narrative texts.

Offload on Paper With Graphic Organizer Lesson Plans

Now that we have discussed how a graphic organizer can help with reading comprehension, let’s talk about some actual graphic organizer lesson plans that your students can do on paper. Just so you know, a group of alternative English I and II education students helped me develop several of these formats I’ll be sharing later on. We’ll be discussing ways to use informational graphic organizers, argumentative graphic organizers and narrative graphic organizers.

Here is a slide deck of some examples that some of my students made: Offloading Working Memory: Charts

Because of previous content and lessons, students realize the realities of how their memories work, the demands of the screen, and the complexities of the comprehension and thinking tasks. Because of this understanding, they are more likely to buy into strategies that they can use on test day, when they are in a difficult mood, or when the text and topics are more robust and unfamiliar. In Reading Recovery, they talk about this concept with decoding. What strategies does the reader know to use at the point of difficulty? It’s not that students have to do all of these strategies all of the time, but internalize them as automatic skills or as resources when struggles arise.

And let’s be honest. The texts we see in STAAR are nuanced. They don’t all follow the same “rules” for text structure and genre. Some of them are even blended in genre, particularly things like memoir used as argument. One method/graphic organizer isn’t going to solve all the problems. I’ve had kids tell me: “I did what the teacher told me to do for annotation. I couldn’t figure it out. It took a lot of time and didn’t help me with the questions. So I thought I was either stupid or this was a waste of time.” The student wasn’t stupid.

The next lesson I share with kids begins with a reminder about the grid experiment. We recall how the grid stores the information about the code that we can use to visualize and recreate the code. The grid offloads the weight of memorizing because it provides a schema to hold the code. We can do the same thing with a text. So we start off concrete and explicit by using paper, folded into the grid. I show them various ways to keep track of information depending on the text and its genre and subtype. We add methods to our collections as we encounter new texts and presentations of ideas. This allows us to discuss the author’s purpose for these genres and structures, and a concrete way for us to select the best delivery system of choices for our own writing.

As I mentioned above, I received help from a group of alternative English I and II education students to develop several of these formats.

Graphic Organizer Lesson Plans: General Notes on Use

Students use the text structure of the passage to determine the genre. They skim and scan to collect available data from the following: title, subtitle, author (sometimes even an agency will be listed, such as National Public Radio), headings, captions, graphics, footnotes, italicized information before the passage begins, citations. All of these provide reliable sources to determine the genre. Here’s how these graphic organizer lesson plans work. First, the student selects the genre. Then they select the best graphic organizer or data-collection mode, prepare the chart, and select their purposes for reading.

Informational Graphic Organizers

Informational texts have common elements regardless of the genre subtype. All passages will have a title. The title will provide a glimpse of the topic and or why that topic is important. The small /t/ represents data that readers can collect about the title. The circle with the three lines under it represents the big idea. Readers can get an initial idea of why that topic matters or what is distinctive about the topic/idea. Note that graphic organizers are not worksh*ts to be filled out. Leaving blanks is ok. The point is to record important information to aid in recall and reference points where the text can be revisited.

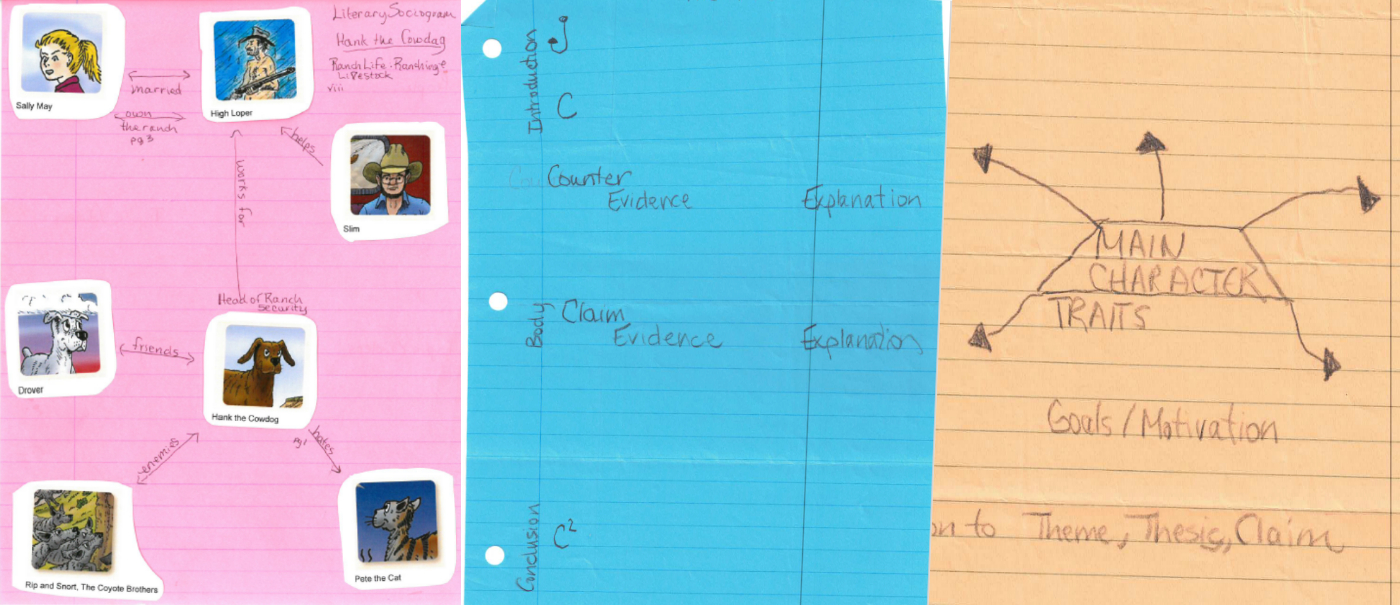

Essay Structure

All informational passages have a similar structure: introduction, body, and conclusion. And each component has similar features. The introduction will include some kind of hook/attention focus or background information. The thesis can be anywhere in the introduction. Or the thesis might not become capable of discernment until the end of the piece. The conclusion will revisit the thesis and come to a satisfying conclusion. Students can list the paragraph numbers in each section as relevant to aid in rereading and reference to text evidence.

Purpose for Reading: When readers begin an informational text, they narrow their focus by reading to find where the introduction begins and ends. Then they read to distinguish between the hook and the thesis.

Connections: Once the introduction has been parsed, readers connect back to the title to confirm or adjust predictions about the topic and big idea.

Changing Purpose for Reading: Once students have verified the thesis, the purpose for reading changes to discover how the writer knows that thesis to be true. Readers use the boxes in the body of their informational graphic organizers to record subheadings if they are present. The reader jots down notes of what the writer says that show how the thesis is true. Note the importance of understanding how informational text structures are used to prove the thesis.

At some point, the reader will realize that the essay is coming to a close. At that point, the reader changes the purpose to validate the thesis from the introduction. The T with the superscript 2 represents the thesis revisited.

Chronological Order

In some informational texts, the thesis is more difficult to discern because the texts are a recitation of events in chronological order. The essay will still have an introduction, body, and conclusion, but the way a reader takes notes may differ in order to collect information about sequence.

Reporter’s Formula

As I’ve worked with students, I’ve found that it is difficult for some to tell if the text is narrative, argumentative, or informational in nature. Or the essay text structure doesn’t seem to fit well for the passage or the reader’s needs. Reporter’s formula (ACTS of Teaching; Caroll and Wilson) helps students select key bits of information on their informational graphic organizers, taking on the role of investigator or reporter. The boxes allow them to draw arrows to connect ideas that aid in making inferences and generalizations about ideas that the other forms of notetaking don’t allow.

The SHBST acronym reminds students to summarize and monitor their understanding of the whole passage. Kylene Beers shared this strategy in When Kids Can’t Read: What Teachers Can Do. It means: Something Happened But So Then. The form also allows students to collect and consider key words or save a place to chunk into syllables for decoding.

The smile, capital I, and stop sign icons help students evaluate the genre and author’s purpose after reading the selection. They consider the summary and all the details and ask themselves these questions: By writing about (this topic) and including (these major ideas) the author intended to entertain me? Give me information? Or convince me to think, believe, or do something? I challenge my kids to STOP and think: You don’t want anyone to take advantage of you. You’d better be beware if someone is influencing you with argumentation.

Note: I recommend using informational graphic organizers for descriptive poems.

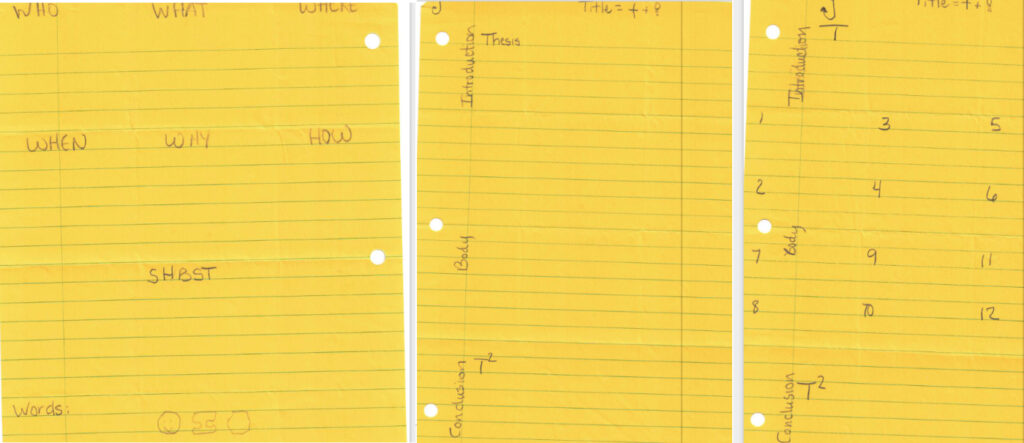

Argumentative Graphic Organizers

The TEKS reference argumentation after 2nd grade. I’m not sure why the assessment division insists on adding opinion and persuasion. The writers of the standards wanted students to focus on source-based reasoning and to move away from opinion and the logical fallacies and techniques involved in things like commercials. But the inclusion of these genres is a reality for now. And I’ve written about it elsewhere. Moving on.

Essay Structure

Argumentative (opinion and persuasion) essays follow similar text structures as informational texts. There will be an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Instead of a thesis, there will be a debatable claim and a particular stance taken in regard to the topic.

In the body, the writer will go about explaining how a person can come to believe such a claim/statement. For persuasion, the writer will talk more about why a person should/could believe an idea, especially with ethos and pathos. Techniques include such examples as bandwagon and other psychological tools. Argument will use logic, reasoning, and empirical evidence: reliable and valid source-based data. Each of these data points will directly reference the claim.

For grades 8 and above, argumentative responses (ECR) will include counterarguments. We might also see counterarguments in any texts that students read in any grade. The counter can appear in any order. It’s important for students to realize how counterargument and other argumentative structures function on their argumentative graphic organizers. Note that evidence and explanation will be present for each key idea that supports the claim.

In the conclusion, an argumentative piece will revisit the claim and come to a satisfying conclusion. In a persuasive piece, we may see a call to action.

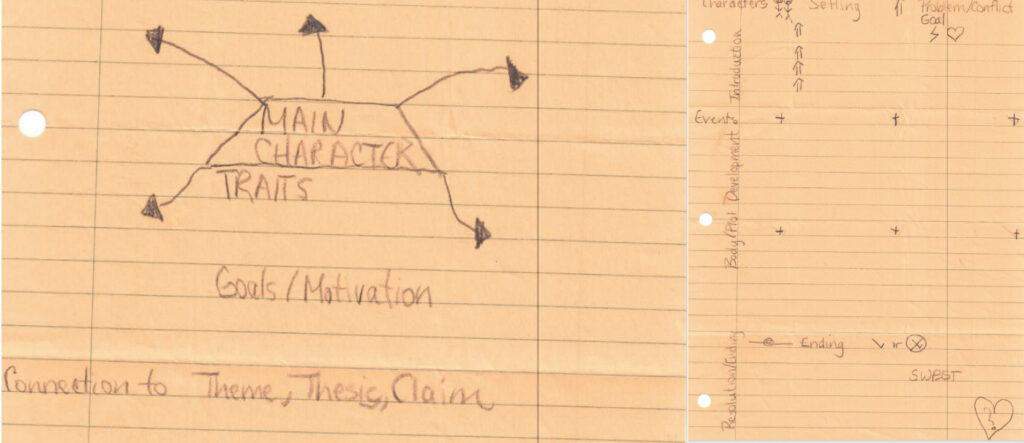

Character Sociogram and Narrative Graphic Organizers

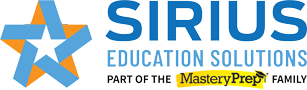

Character Sociogram

I have to admit. During and after reading, I often cannot remember the names of characters. I find myself seeing a name in subsequent chapters and asking myself, “Who was that, again?” And some of these names in passages … hard to even pronounce. Some of my kids struggle with the same things. Who is who? A character sociogram takes care of a lot of this, even when the text isn’t a narrative one. Often, anecdotes and reports of real people appear in informational and argumentative texts. We’ve also seen memoir function as argument. Keeping track of the characters is key to theme, purpose, and message for all kinds of texts.

A character sociogram begins by putting the players on the field like a baseball diamond. The main character is the pitcher. As the pitcher, the main character connects to all the other positions in the field. In narrative, we call this “relationships.”

To use these narrative graphic organizers, readers write down the main character’s name in the center box. They collect information about the character’s traits, goals, and motivation. (After all, plot is what happens to characters as they go about getting what they want and need (Kendall Haven)).

Then the reader charts the other characters and interactions in the boxes. They label the arrows with relationships including friend, coach, mother. Names, traits, actions, and other ideas can be added about the new characters and how they are involved in the character’s search for the goals.

At the bottom of their narrative graphic organizers, readers are encouraged to consider why this character was specifically chosen to deliver the theme or support the thesis/claim. You see, it’s not just about collecting data. We want kids to think beyond plot points and toward why they matter in life lessons/theme. We want kids to think beyond facts and toward how they are used to convey big ideas.

Memoir

Memoirs are weird, y’all. They look like stories. But they are doing so much more.

Narrative

Narrative graphic organizers helps readers collect and offload data about stories (and narrative poems). Students begin by looking for the characters, setting, and the character’s goals and motivation. They consider what is getting in the way of the character’s goals and motivation to find the conflict. When we annotate physical texts, students draw stick people and add smiley faces for the protagonists and frowny faces for the antagonists. For the setting, students annotate with stick figure houses. My alternative students selected a lightning bolt for conflicts, hearts for character motivations and goals, and a heart with a lightning bolt through it for when the character encounters the series of struggles.

It’s important to note also when setting changes, as it impacts character actions, conflict, and visualization. So we ask kids to note when a setting changes on their narrative graphic organizers.

Once the students have discovered the characters and conflicts, they change their purposes for reading: How does the character get or not get what they want? We list those main action items in the plot with plus signs. Again—not all boxes need to be filled out.

At some point, the readers will discover the very moment the character succeeds or fails. This is the climax and signals the conclusion. I’m still fond of the denouement, so I draw a knot of all the loose ends coming together. From here, students consider the summary and why it matters. I ask my kids: So what? Who cares? They use Beer’s SWBST (Somebody Wanted But So Then acronym to summarize) and then think of why they should take the ideas to heart (theme).

The Magic

So, why did we do all of this work? Were these graphic organizer lesson plans worth our time? I find that teaching this kind of annotation, purpose setting, and extended thinking helps internalize the structure. I used to get mad because they didn’t use the paper on the test. But what I found is that most kids didn’t need it anymore. The work had changed the way they consumed texts. Others just used bits and pieces of the charts when they had difficulty.

But, for complex texts and the questions, this charting had an outcome I didn’t expect. Especially for paired passages. Students could physically point to places on the chart where they needed to compare characters or ideas. They could find the answers without skimming and scanning the text again. Or they knew where to look in the text to find answers. In one test class with special education students who were nonverbal and who could not read, 6 out of 7 of the questions we needed to answer from the grade-level passage were already on our charts. Students could point to the location of the answers and evidence, proving they could master those standards even though they could not speak or read. You wouldn’t believe how excited they were to engage in such complexity with ease.

With my other students, they saw why the charting was worth their time when it came to answering questions. Especially when they realized that they had written the major reasons and ideas they could use in the written responses.

Some of them still didn’t buy into using paper during the test. So we came up with some strategies they could use online. We’ll share those ideas next.

TEKS Commentary

Foundational Language Skills: Fluency: A

Foundational Language Skills: Self Sustained Reading: A

Comprehension Skills: All of them. The self-selected tools and approaches help students make important decisions about texts for themselves that lead to deep comprehension. These graphic organizer lesson plans not only free up working memory, but are processing the type of comprehension skills and finding answers before they are even asked a single question.

Response Skills: B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J: By adding genre characteristics, adjusting purposes for reading, and considering theme, message, and purpose, learners develop the habits of mind, internal processes that preceded the ability to answer multiple-choice questions about comprehension.

Multiple Genres: Literary Elements: A-D

Multiple Genres: Genres: A-F

Author’s Purpose and Craft: A, B, C; Other elements of APC are best evaluated and analyzed after basic comprehension and consumption of text are complete. It’s very difficult to take in the ideas and follow the plot while simultaneously analyzing craft. It’s best do comprehend before analyzing.

Composition: Writing Process: The annotations and considerations function as prewriting.

Composition: Genres: B, C, D: The annotations and considerations function as the reasons, details, and organizational structures to be used in both short and extended constructed responses.

Next Up

Now that we have discussed some graphic organizer lesson plans that students can follow on paper, next time, we’ll talk about how they can demonstrate annotation methods using online tools. Hopefully you found this break down of the best ways to use a character sociogram, argumentative graphic organizers, informational graphic organizers and narrative graphic organizers.